#Gothic horror as in actual Gothic horror and all the thematic elements that implies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gothic horror wizard101 fanfiction but not in the Tumblr way

#Gothic horror as in actual Gothic horror and all the thematic elements that implies#Hi I'm still leafing through old fics and found the one where the death school house has a backstory#I get really annoyed when I try to search the Tumblr tag for gothic horror#And I see reposts of videogames and tv shows that are certifiably Not Gothic Horror#I'm pretentious but at least I know what the fucking genre is#It annoys me fr because#You love gothic horror but hate anything that addresses racism and colonialism and patriarchy#With the full despair those concepts demand

1 note

·

View note

Text

TerraMythos 2021 Reading Challenge - Book 10 of 26

Title: The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890)

Author: Oscar Wilde

Genre/Tags: Fiction, Gothic Horror, Third-Person, LGBT Protagonist (I... guess)

Rating: 8/10

Date Began: 4/13/2021

Date Finished: 4/20/2021

When artist Basil Hallward paints a picture of the beautiful and innocent Dorian Gray, he believes he’s created his masterpiece. Seeing himself on the canvas, Dorian wishes to remain forever young and beautiful while the portrait ages in his stead. The bargain comes true. While Dorian grows older and descends a path of hedonism and moral corruption, his portrait changes to reflect his true nature while his physical body remains eternally youthful. As his debauchery grows worse, and the portrait warps to reflect his corruption, Dorian’s past begins to catch up to him.

Perhaps one never seems so much at one’s ease as when one has to play a part. Certainly no one looking at Dorian Gray that night could have believed that he had passed through a tragedy as horrible as any tragedy of our age. Those finely-shaped fingers could never have clutched a knife for sin, nor those smiling lips have cried out on God and goodness. He himself could not help wondering at the calm of his demeanour, and for a moment felt keenly the terrible pleasure of a double life.

Full review, some spoilers, and content warnings under the cut.

Content warnings for the book: Misogyny (mostly satirical). Racism and antisemitism (not so much). Emotional manipulation, blackmail, suicide, graphic murder, and death. Recreational drug use.

Reviewing a classic novel through a modern lens is always going to be a challenge for me. The world seems to change a lot every decade, let alone every century—whether some canonized classic holds up today is pretty hit or miss (sorry, English degree). And considering the sheer amount of academic focus on classic texts, it’s not like I’m going to have a “fresh take” on one for a casual review. I read and reviewed The Count of Monte Cristo last year, and thought it aged remarkably well over 170+ years.

Somehow I never read Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray for school. I tried reading it independently in my late teens/early twenties, and honestly think I was just too stupid for it. Needing a shorter read before the next Murderbot book releases at the end of the month, I grabbed Dorian Gray off the shelf and decided to give it another shot. By the end, I was pleasantly surprised how much I liked the book.

I’m actually going to discuss my pain points before I get into what worked for me. The first half of the book is very slow-paced. The Picture of Dorian Gray is famous for… well… the picture. But it isn��t relevant until the halfway point of the novel, when Dorian does something truly reprehensible and finds his image in the picture has changed. There’s a lot of setup before this discovery. The first half of the book has a lot of fluff, with characters talking about stuff that happened off screen, discussing various philosophies, and so on without progressing the story. Some of this is fine, as it establishes Dorian’s initial character so the contrast later is all the more striking. I just think it could have been shorter. I realize this comes down to personal taste.

I’m also torn on the Wilde’s writing style. He’s very clever, and there are many philosophical ideas in his writing that did genuinely made me stop and think. The prose is also beautiful and descriptive; this is especially useful when it contrasts the horror elements of the story. However, there’s a lot of unnatural, long monologue in the story. Not sure if it’s the time period, Wilde’s background as a playwright, or just his writing style in general (maybe all three), but the characters ramble a LOT. My favorite game was trying to imagine how other characters were reacting to a literal wall of text.

I also feel the need to mention this book has some bigoted content, as implied in my content warnings. The misogyny in the story is satirical; it’s spouted by the biggest tool in the book, Lord Henry, whose whole shtick is being paradoxical. You just need basic critical thought to figure that out. However, some things don’t have that excuse. A minor character in the first half is an obvious anti-Semitic caricature. There’s also some pretty racist content, particularly when Wilde describes Gray’s musical instrument collection. While these are small parts of the book, it’d be disingenuous not to acknowledge them.

All that being said, there were many aspects of the book I enjoyed, particularly in the second half. Wilde does a great job characterizing terrible people who fully believe what they say. Lord Henry is an obvious example, and Dorian follows his lead as the story progresses. One of my favorite bits was after Sibyl’s suicide (which Dorian instigated by being a piece of shit). Dorian is initially shocked, but as he and Lord Henry discuss it, they come to the conclusion that her suicide was a good thing because it had thematic merit. It’s just such a brazen, horrible way to alleviate one’s guilt.

Dorian also goes to significant lengths to justify his actions. At one point, he murders Basil to keep the portrait a secret. While he briefly feels guilty about this, Dorian grows angry at the inconvenience of having killed this man, supposedly an old friend. He even separates himself from the situation, expressing that Basil died in such a horrible way. Bro, you killed him! It was you! The cognitive dissonance is just stunning.

It’s also viscerally satisfying to read about Dorian’s downfall as his awful choices catch up to him. Dorian becoming tormented by the portrait is just... *chef’s kiss*. Is it surprising? No, it’s pretty standard Gothic horror fare. But there’s something to be said about seeing a genuinely horrible man finally pay for what he’s done after getting away with it for so long. I wish real life worked that way.

There’s the picture itself, too. I know it’s The Thing most people know about this novel -- but I just think it’s a cool concept. I like the idea of someone’s likeness reflecting their true self, and the psychological effect it has on the subject. Most of the novel is fiction with realistic horror elements, but I like that there’s a touch of the supernatural thanks to Dorian’s picture. It’s an element I wouldn’t mind seeing in more works.

It's sad to read Dorian Gray with the context of what happened to Wilde. The homoeroticism in the novel is obvious, but tame compared to works today. Wilde and this book are a depressing case study in how queer people are simultaneously erased and reviled in recent history. Wilde was tortured for his homosexuality (and died from resulting health complications) over 100 years ago, yet the 1994 edition of Dorian Gray I read refers to his real homosexual relationship as a "close friendship". It's an infuriating and tragic paradox. Things have improved by inches, but we still have so far to go.

As I grow older I find I appreciate classic works more than when I was forced to read them for school. The Picture of Dorian Gray is a gripping Gothic horror story. Some aspects didn't age particularly well, but that's true for almost anything over time. If you're in the market for this kind of book, I do recommend it.

#this review is late but in my defense the nier remake came out#taylor reads#2021 reading challenge#8/10

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad at 34

A review by Adam D. Jaspering

The 1940s were a troubled time for Disney Studios, financially. Through deal-making, patience, and budgeting, Disney Studios endured a dark age and righted themselves. By 1949, they were free to return to the path established at the decade’s beginning.

Abandoned interpretations of Cinderella, Peter Pan, and Alice in Wonderland started up again. Production began on Disney’s first completely live-action film, Treasure Island. True-Life Adventures, a series of documentary shorts, were a surprise hit. The 1950s were going to be very kind to Walt Disney and his company. But they weren't there yet. There was one final task before Disney could shut the door on the 1940s.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad was to be the final package film from Disney, closing out this era. The movie is comprised of two shorts: The Wind In the Willows, and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. The two shorts have no thematic link besides being literary adaptations. For much of its development, it had the working title Two Fabulous Characters.

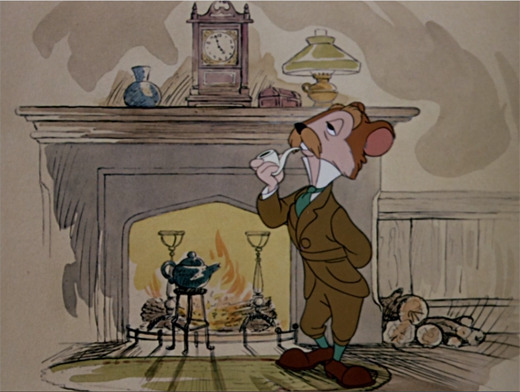

The Wind In the Willows is an adaptation of the 1908 children’s book by Kenneth Grahame. The story centers around a quartet of animals living in Edwardian England. The sensible MacBadger, Ratty, and Moley try their best to help their outlandish and boisterous friend, Mr. Toad. Basil Rathbone narrates the short.

At various points of its production, Disney Studios intended to adapt the book into a full-length movie. The troubles at Disney Studios and a string of creative blocks impeded its completion. At the insistence of Walt Disney himself, it was finally scaled back to a half hour short.

The Wind In the Willows has a level of appreciation in its native Britain, but in the United States, it’s a somewhat obscure novel. Much of its substance relies on a knowledge of British customs and sensibilities. This cultural disconnect makes it relatively inaccessible to American children. For a book featuring talking animals, a runaway locomotive, and a prison break, there is a large focus on manners and dignity.

Being an American production company, Disney Studios had an uphill battle. They not only had to produce the ostensibly British work, they needed to deconstruct it. They couldn't just deliver the story, they needed to present it in a way that could be understood by children internationally. A comedy of manners doesn't work if one doesn't understand the setting and society. Disney does not deliver in this regard. Everything comes across as British for British sake.

The character MacBadger is voiced by animator Campbell Grant. Grant had been working with Disney since the Hyperion Studio days. He was born in Berkley, California, and never lived in Scotland. His talents as a voice actor reflect the fact. He provides an incredibly forced and painful Scottish brogue.

On the other hand, Ratty has such a perfect English accent, it’s almost a parody. Ratty is voiced by Claud Allister, an actual British actor. Allister seems determined to perform the most stereotypical British character ever witnessed by an American audience. Ratty has a stuffy London accent, smokes a pipe, wears a deerstalker cap and wool suit, has a bushy mustache, aristocratic mannerisms, and regularly hosts tea. Is English his nationality, or his personality?

The other characters (minus the Scottish MacBadger) are English as well, but allowed other traits. Is Ratty a joke? Is he meant as an object of ridicule? Is this Disney's attempt at societal farce? His characterization is confusing and doesn't help the story.

The main character, touted as ‘fabulous’ by the film’s working title, is Mr. Toad. Mr. Toad is an individual of great wealth. Old family money, to be specific. He has no work ethic, no discipline, and is intent on spending his fortune and his days as recklessly as possible. MacBadger, Ratty, and Moley spend their days cleaning up Mr. Toad’s messes and curtailing future mistakes.

The relationship between these four is something of a mystery. Ratty and Moley appear to be roommates. MacBadger operates as accountant of Mr. Toad’s estate, apparently a long-time employee. But how all four came to meet is never fully explained or implied. For the purposes of the film, they are burdened with Mr. Toad and his antics. This is their lot in life.

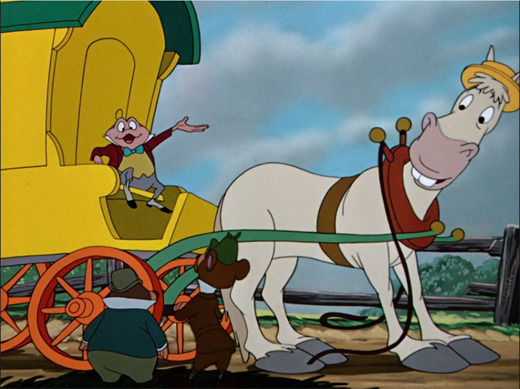

Mr. Toad is a vivacious individual who’s quick to jump on frivolous trends, indulging his whims at a moment’s notice. He spends way too much money on ostentatious displays of conspicuous consumption. We’re introduced to him, rampaging down the road on a horse-drawn carriage. Ratty and Moley beg and plead for him to stop, as he is causing an alarming amount of property damage. Mr. Toad scoffs at their request.

But Mr. Toad's interest in his wagon is halted by another method. Seeing an automobile, his appreciation for wagons disappears. He becomes maniacally obsessing over owning a car. Ratty and Moley intervene again, locking Mr. Toad in his bedroom as though he were an addict detoxing. Mr. Toad's fits are a nice piece of visual humor, but don't endear the viewer to his selfish behavior.

Mr. Toad escapes out his window, finding a tavern full of literal weasels ready to sell him the stolen car. The weasels are stock criminals. Their purpose is to distract the viewer. To trick them into not suspecting the true villain of the feature. The deceit is ineffective, not from a narrative standpoint, but an animation standpoint.

The bartender is one of the most on-the-nose designed characters in the history of animation. His treachery is supposed to be a surprising plot twist, as though we could not see it coming from miles away. The man practically has "villain" tattooed on his forehead. With his squinty eyes, malicious grin, hunched posture and arched eyebrows, the animators did not give their audience any credit. Anyone who could not come to the independent conclusion that he is a con man deserves to be ripped off.

Mr. Toad's friends are forced to intervene again, testifying on his behalf. To no avail. Mr. Toad is arrested, but escapes from prison in an effort to prove his wrongful conviction. MacBadger, Ratty and Moley are tasked one final time to reverse Mr. Toad's fortune and prove his innocence. It is a very one-sided friendship.

Mr. Toad eventually clears his name. He doesn’t learn any lesson, immediately returning to his old imprudent lifestyle. Mr. Toad experiences no consequences, and suffers no losses. His friends don’t think any less of him. They receive no reward for their faithfulness. Our heroes end up exactly where they had started.

The Wind In the Willows is an adventure where somehow nothing happens. There’s no moral, no journey, no change, no growth. It’s a chapter from the characters’ lives. It feels immaterial.

Perhaps Disney Studios expected to reuse the characters in the future. Only a portion of Grahame's book is represented in the cartoon. The Wind In the Willows could conceivably be a franchise. Story elements cut from the original feature-length script could be repurposed into one or two additional shorts.

If this was the plan, of course the writers needed to hit the reset button. Viewers wouldn't understand a follow-up cartoon if they hadn't seen the predecessor. The shorts would need to operate independently as well as part of a series. The characters end here unaffected, consequence free, but primed for another outing later.

If this was the plan, nothing came to fruition. As Disney presents it, The Wind In the Willows is an abandoned pilot. It's the pointless story of an unlikable amphibian and his overburdened friends. A good story makes you glad you went on the journey. The Wind in the Willows is the equivalent of walking into a room and forgetting why.

The production of The Wind In the Willows continued off and on beginning in 1938. Walt Disney himself was rather indifferent to the source material. He only optioned the film rights for financial opportunity. Ironic, as the production was a complicated, eight-year boondoggle.

At various times, it was intended to be paired with Mickey and the Beanstalk or Pecos Bill, and released as early as 1946. For varying reasons, it wasn’t released until 1949, when it was paired with another short entirely.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow had a much simpler production history. There was no logical way to adapt the 24-page short story to a full-length feature. From the beginning, it was intended to be a short. Production began in 1946. In 1947, Disney decided it would accompany The Wind In the Willows to the big screen.

Why pair these two unrelated shorts together? There’s no official justification, but one can deduce their intention. Disney Studios was sick and tired of package films. They wanted to move on. They didn't want to spend a single extra minute supporting them. They had two shorts completed, ready for distribution. It didn't matter how disconnected they were in subject. Sometimes art is a labor of love. Sometimes you want to end the creative process as fast as possible.

Referred to as Ichabod Crane by the film, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is based on the 1820 short story by Washington Irving. The story centers around a superstitious schoolteacher, Ichabod Crane. New in town, he vies for the romantic attention of a wealthy heiress, Katrina van Tassel. Crane is impeded by local townsman Brom Bones, also courting Katrina. As the contest grows to a head, a mix of animosity and local legend decides the fate of Crane.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is one of the earliest pieces of American literature to be regarded as a classic. It remains a staple of the gothic horror genre. The featured monster, The Headless Horseman, remains a chilling figure in the horror pantheon. What's more, the Disney version is considered the definitive adaptation and a Halloween staple.

With such an established holiday association, it’s easy to forget that all mentions of Halloween don’t occur until halfway through. More than that, the iconic ride of the Headless Horseman lasts seven minutes. The first half of the story is nothing more than a typical love-triangle. Just set during the Washington administration.

It’s a testament to great storytelling and memorable characters. Half the picture is establishment and foreshadowing, but never feels plodding or pointless. It all builds, shapes the world, and pays off spectacularly at the end.

The physical appearance of Ichabod Crane is a master stroke of design. Crane is tall, rail thin, with long legs, and a large nose. He looks every bit like the bird he shares a name with. He looks odd, comical even, but not out of place among the other citizens of Sleepy Hollow.

It’s part of his charm that such a gangly, awkward fellow is depicted as a classy, desirable man. Him being voiced by Bing Crosby is a large element of this attraction. It’s not stunt-casting. The disconnect between a major celebrity’s charisma coming from the mouth of a laughably ungainly character is fantastic. It’s just one great element of an intricate character.

Every time we think we understand who Crane is, we learn something new to smash those conceptions. He’s a man of letters, but also superstitious. He’s a romantic, but also deviously wants to marry Katrina for her money. He’s a disciplinarian, but easily swayed by his own interests. A running gag demonstrates he values food over everything. Crane is an enigma.

In contrast, Brom Bones is an archetype. There’s not much to comment on. He’s a burly man, popular with the townsfolk, prone to violence when challenged. He's singularly focused on a specific woman who barely gives him attention. We’ve seen this archetype already with Lumpjaw in Fun and Fancy Free, and we’ll see it again in Beauty and the Beast.

And yet, Brom Bones surprises us by transcending his himbo personality. He displays a precisely-executed bit of cunning. Brom takes advantage of Crane’s superstitions, reciting the story of the Headless Horseman at a Halloween party. With perfect delivery and cadence. He captivates the townsfolk with his tale, but leaves Crane paralyzed by fear.

The final climax features a sense of ambiguity outshining Irving's original story. It’s strongly implied that the Headless Horseman is truly a myth. That Crane experiences no supernatural entities. Instead, it's Brom Bones in disguise who terrorizes Crane on his way home. It's the second half of his scheme, causing Crane to flee town, leaving Brom alone to marry Katrina.

It's strongly implied, but not definite. One may also choose to believe the Headless Horseman is real. That Crane did indeed meet his doom on Halloween night. It’s open for interpretation, and both are viable. Even if one is slightly more credible than the other.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is a fantastic short. Ichabod Crane is interesting and complex. The environments are lush and evocative of a New England autumn. The story is fun and engaging. Its final act is atmospheric and chilling. It's the perfect introduction for children to the horror genre, and holds up to adult sensibilities. It deserves to be watched once a year. But just like with Disney’s other package films, a great short is better enjoyed separated from a crudely assembled movie. And The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is as crude as they come.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad was the last in a long march of frugal package films. Mandated by financial constraints, everyone knew they were low-effort affairs. Thankfully, Disney Studios could pursue ambitious productions once again. Disney would not produce another package film until 1977, when the studio encountered similar financial problems. But in 1949, the era was finally behind them. The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad wasn’t meticulous, wasn’t neat, and wasn’t even coherent as a feature. But it was a film. Disney shut the door on the era with a resounding slam.

Fantasia Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio Bambi The Three Caballeros Dumbo Melody Time Saludos Amigos The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Fun and Fancy Free Make Mine Music

#The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad#The Wind in the Willows#The Legend of Sleepy Hollow#Disney#walt disney#Walt Disney Animation Studios#disney studios#Film Criticism#film analysis#movie review#Disney Canon

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writer Notes: The Wicked + the Divine 40

Spoilers, obv.

The first issue of "Okay." I've known for quite some time that it was likely the final arc would use the word "Okay" in some way. The unpacking phrase "It's going to be okay" has been a backbone of the series. Due to the first year on the book, that's been a loaded phrase, all the way through.

But when signing a first volume of the book, I've added the dedication "It's going to be okay." There's lots to unpack in that, and I suspect I'll wait until later in this arc to say any more. But knowing that eventually we'd like have an arc called "Okay" was definitely part of doing it.

The quotation marks are key. It's a move I've done a few times in my career, in terms of showing it's a story that wants to highlight something, and raise awareness that the word should be approached with conscious consideration. This is a choice. I want you to know it's a choice. Let's talk about what that actually means anyway, right?

It's a technique I first lifted from Bowie's "Heroes". Which, of course, is doubly appropriate to use it at the end of WicDiv.

We knew they'd be a gap between the end of Mothering Invention and the start of this. The remaining five issues of the arc were tightly plotted, but in the document, this is the one which I left a lot open. I knew what I wanted to be, and it was a chance of finding an execution to make it work. It was a last chance to do a big concept issue.

(Which isn't to say there isn't conceptual stuff elsewhere in the arc. There just isn't a whole issue of it.)

This is something that I've been trying to do since issue 6. As in, a purely fan-centric issue of mainly talking heads. Every time, it's had to be cut for space. The talking heads shots of realistic footage, showing a lot of fans views on the matter. You get ghosts of it – any time Beth turns up, you get some, basically, but all of those moments could have been issues in another version of WicDiv.

(The one we won't be doing is the whole issue of literal talking heads. As in, Tara, Lucifer and Inanna just telling stories. That's fun, but we just don't have the time, and when I realised I had to stop them talking, it was definitely out. Oh, Minerva. You spoil everything.)

Equally, WicDiv's a book with two poles – the modern fan pop cultural part and the mythological grandeur. We swing one way or another, and it's easy for the latter to mug the former. I suspect that's because that's the easier stuff. Especially as Laura has gone down her hole, she's been incapable of seeing the good parts of fandom. An issue of that before the end, seemed necessary.

(Equally, with where it goes. Like, we start with Laura as a fan, and end with her on stage, saving people. The Bowie Saved More People Than Batman of WicDiv. It's a book about cycles, and ever more so here.)

So! The other side is this apocalyptic final scheme, and give a perspective on that – the necessary plot. Equally, keeping Laura off stage as long as possible.

So we end up with this.

I knew wanting to pick up and run with minor characters in WicDiv was something I wanted to do, and merging it with a disaster rapidly led to something else – this is clearly an inverted Watchmen 11. There, they gather the supporting cast together in the b-plot and then with a I-did-it-35-minutes-ago kill them all. We flip that. We imply everyone we're watching is dead, reintroduce the whole cast and then have Laura save them.

Suffice to say, formally, this was tricky.

Jamie and Matt's cover:

Meet Tom. We surveyed the whole supporting cast and picked someone who was present enough in a scene to be likely to be remembered but minor enough to be a surprise. In the end, there were less options... and the kid who asks Persephone about what to call her obviously has some strong thematic elements. She told him something. What did he make of it? It also gave a supporting cast of friends.

It's fun doing a cover like this and people going "who the hell is he?"

I wish he wasn't white and male – if I realised I was definitely going to use him in issue 24, I'd have likely have suggested otherwise. But, on the other hand, there is a point that white male guys should have heroes who aren't white male guys. So maybe I'm okay with it. Comics!

Claire Roe's Cover Well, this is monstrous. You do get the image of Minerva, like she's in Home Alone, trying to smuggle skulls. Just some great images here.

Ray Fawkes' Cover

For the Heroes Inititative Charity. The theme was "Giving" which immediately jumped to a "Lucifer giving an apple." Giving is very loaded for us. Ray is amazing – he's been an incredible support throughout all of WicDiv, and we love him. Go buy his books. My favourite is THE PEOPLE INSIDE, but for something more genre, the UNDERWINTER books are fascinating, horror. UNDERWINTER: SYMPHONY is the adult gothic sister of Wicdiv, if you squint.

IFC

Flipping "Ascended Fangirl" into "Descended God" was sitting in the script for this issue before anything else.

Page 3

Black page with white text is something that's come to the fore in the last year of WicDiv. In here, the exact word choice was key. While this feels like a documentary in terms of how it arranges information, the text doesn't tell you that. It tells you it's just footage. This means that it's not necessarily an in-world document.

Page 4-5

Working out the exact panel dimensions was a nightmare, and led to a couple of rewrites to move some pages from eight panel to a more accurate six panel. You can also see Jamie start to wrestle with the unique horror of drawing stuff that is slightly distorted, choosing angles which are less traditionally interesting and so on.

Unboxing videos are a fascinating phenomena. It's fun to see culture happen which I fundamentally don't get on an emotional level. That's what culture should throwing up.

The details on the ticket do make me smile, in an awful way.

Yes, the "change the orientation" panel is clearly us showing off. This is the sort of issue I did a lot of doodles for. It also led to a bunch of lettering challenges for Clayton, in working out whether to put balloon tails off-camera to signify the other speaker. In the end, Clayton talked us into the other approach, noting it worked fine in Mister Miracle. Hey, if Tom King does it, I guess it's fine with us.

It's worth noting the way the off-panel speaker is orientated, to ensure you know who they are. See the "Tom" in the dialogue in the second panel, to ensure you know it's Nathan.

"The front row if it kills us" is very us. This issue is a mix of awful tension and strokes of equally awful gallows humour. His smile is also adorable.

Page 6

Sometimes the most beautiful thing in the world is a page of exposition via the medium of power-point. We're all big fans of the 1960s kirby superhero maps, and this is kind of the same thing.

Page 7

This is also a masterclass in a "Naturalism is hard" sort of page layout. The choice of the greys by Matt is really nice too.

Page 8

And back with Tom and friends. Worth noting the planning on this issue – I had this list of scenes, and tried to work how much I can cut between them to create a rhythm, which obviously accelerates the further we go in.

"Shitting them whole"? Nathan is totally right. Tom, you re NASTY.

Trying to get a subplot which fit in the space for them is key. Like, friends navigating a space. That Tom and Nathan are both far from perfect in this is also important. I just realised this is totally an alt-dimension Kohl and Kid-with-knife scene.

Page 9

The greatest tragedy of WicDiv is we never got around to doing the WicDiv calendar with all the dates on. Will we get around to it for Christmas 2019? IT COULD BE POSSIBLE.

The problem in terms of story here is getting the multiple lies – Woden doesn't know what Baal has had him to do, and Baal doesn't know what Minerva is making him do. So trying to set that information up so is clear, while also in a naturalistic fashion is a trick.

We were having LOC CAPs on some of this footage, but decided to cut them all. Only some of them had it, and having it on them all would create a mess. This is the one I regret though – there's one tiny bit of information I'd like to have got in here. C'est la vie.

The colour banding on this is fascinating – the late night recording. Also, Jamie's burn on the calendar is golden.

Page 10

This was another one where the lines were worked hard. What happens BEFORE the image, what happens AFTER the image and all that.

Anyway, some good thinking here Tom.

The chat between the two, in terms of fans-beliefs and minor pieces, and hot takes and their own beliefs. Also re-introducing certain takes.

Page 11

This page is hard. The silent third panel is amazing – what Jamie does with the panning between the two. The caption would have revealed who's filming it – the Sister – but that isn't essential information.

"You soppy twat" is something I'm oddly pleased with getting in. It's a very naturalistic issue, and the tenderness is very real.

There has been a tendency for people to take Baal's fight against the Great Darkness solely to save his family, and understandable why. This scene and what follows shows that no, it's not just that. He actually believes he's saving the world, because if he didn't, he certainly wouldn't fucking do this.

Page 12

And Minerva reveals her side of all this. The little callback to 1373 does make me smile.

The stylistic nature of this is key – Jamie doing the fish-eye, Matt working the blues, giving that night vision creepiness.

Page 13-14

This issue was definitely me trying to look for ways for Jamie to not just draw a million crowd-scenes. The first two is definitely me lampshading it.

In passing, this two pages is basically all of Young Avengers in sixteen panels.

The last panel is a thing of love, and definitely inspired by a Glastonbury festival, circa 1998. I'm there alone, as it was one of the infamous wet years, waiting for Nick Cave to come on the main stage. A highly high and/or drunk guy stops beside me, after pushing through the crowd. He's clearly very excited, to the level where a group of younger women start to join in and/or mock him. He is very entertaining.

Nick Cave comes on stage, doing a half-speed From Her To Eternity.

"From her."

"To."

Eternity."

Murmurs Nick.

Our new friend hasn't actually noticed and howls at the top of his lungs...

"FROM HHHHEERRRRR TOOooOOOOOOooOOOOOOoo ETERRNNITYYYY!"

...at at least twice the speed of Nick.

At which point, he's decides he wants to be further front. Turning to the people around him, he suggests we all go forward. "Yeah?" "Yeah!" the girls scream, and immediately they all form a conga and start pushing through the crowd, with him chanting "NICK CAVE ARMY COMING THRUUUUUU!"

I join in, as clearly I want to follow this journey. It leads us to the front, where I believe I stay for the rest of the night?

On the way to the front I step on the shoe of a guy who, a year or two later, invites me to storm the stage on a Saturday morning TV show. I turn it down, and then he only goes and does it anyway.

Pop music!

Anyway, that panel is for that guy, wherever he is.

Page 15

Okay, I can't hold off crowd scenes forever. Sorry Jamie, but not too sorry, as this looks amazing. Matt pushing the controls completely into the red, with the distortions going on. This is everything. It's also the panel where the conceit of watching television is lowest – the panel shape is wrong, and it's unlikely a camera would be on Baal's mum on the top of the pillar... but they are deniably so, I suspect.

I look at this page and smile. This is some comics. Nice work, us.

Page 16-17-18-19

And we're off. This is... oh, god. There were diagrams for this, in terms of working out panel flow. There's multiple routes through the two pages, which cascade together. The backbone is the "Baal" story arc, across the diagonal on both spreads.

The second panel reads across both pages – notice the orange band leading you to the right – where a talking head explains what's actually going on at the gig, and why everyone is being immersed.

When you finish this row, you get the presenter giving the context for the remaining talking heads. On the first spread, you get a talking head talking answering the question... and then placing them in the crowd. When that ideas's been set up, in the second spread we have multiple talking heads answering it, which all gather around a single group shot showing them all by each other, unknowing. And then there's Tom, and his friends, mixed in, with Tom's own answer stumbling towards his own truth, and his friends together, joined in this.

I'm getting excited here, clearly, but this is some engineered machine monstrosity, and I love how it collaborates with the reader.

This made it a nightmare for the guided view on Comixology. We contacted them in advance, offering to help a little. In the end, I wrote my suggested route, and they went with it. Moving from a non-linear sequence to a linear sequence clearly changes it somewhat, but I think it keeps a lot of the percussion. So don't blame them, blame me.

Oh – I had a list of people to possibly include in this sequence, and selected from them. There's been some impressive attempts by readers to ID everyone. Clearly, I tried to signal who they were in their dialogue a little. My personal hero is the guy from issue 19 who saw Dionysus before Baph nabbed him. You're a fucking legend too, mate.

Tweaks we did was realising it was three hetero-reading couples on the first page, which was heteronormative. We changed that to avoid it. And, yes, that's Jon's mum.

The one I wished I could get in, but lost, was the guy standing to the right of Laura in Issue one, who jizzed to Amaterasu. His line would have been something like "I hope I enjoy this one as much as that time with Amaterasu!"

This is an awful book, in many ways.

20-21

And just let the awful moment linger. Do it naturally and show it. All that rush and then this. Once more, Matt Wilson for Eisners. The hyperbright is one thing, but the flicker on the aftermath another. And the hint of the giant in there is also carefully worked – it's something we needed there, but also was a small part of it. What was important just imagining all those people dying.

22

Inevitable Total Eclipse Of The Heart reference, the go-to song for ending WicDiv dance parties.

23-24

And then, after all that, we get this moment, building towards that final image of Laura.

Honestly, this got to me when Jamie first sent it to me in a burst into tears way. You've come a long way.

I also like the idea that Laura, before heading out, looked through all her stuff and decided "Yes, Hoop ear-rings are the look for saving 20,000 people."

Next issue is out on Wednesday.

Thanks for reading.

142 notes

·

View notes